NYC Chinatown: (Not) for Your Consumption

Paying tribute to a neighbourhood is to embrace wholly—no digital brushing needed

I wasn’t sure if I was going to have a post this week, but seeing fashion designer Prabal Gurung tout his love for Manhattan’s Chinatown, all the while purposefully erasing it through photography for his Resort 2022 collection, had me in such a state of unease that I wanted to comment on it.

While Gurung’s comments to Vogue, block-quoted below, could be perceived as uplifting, the images, particularly the two that I want to unpack here, reveal something that does more so the inverse through its erasure a neighbourhood’s lived narrative.

I used to live in Chinatown, right before I launched my collection. That’s where I started to plot and plan what I wanted my career to be, but I was fully aware of how invisible the community was to the rest of New York. When we talk about the city we talk about the glitz and glamour, but its grit and the character is in neighborhoods like Chinatown. I wanted to celebrate that.

To contextualize what it means to show off or visit New York’s Chinatown, we have to understand this historical morsel: throughout the 19th century, slumming was a popular past time for New York’s wealthier uptown residents to participate in what was essentially class tourism. Horse-drawn carriages would guide “tourists” through Chinatown’s narrow streets, allowing them to to gawk from above at what and who they saw as different and “exotic”. It’s not so much that the community was invisible to the “rest of New York”, as it was continuously positioned as foreign, with its residents essentially casted as outsiders whilst trying to survive and navigate an immigration system that explicitly targeted them.

What do we see (or not see)?

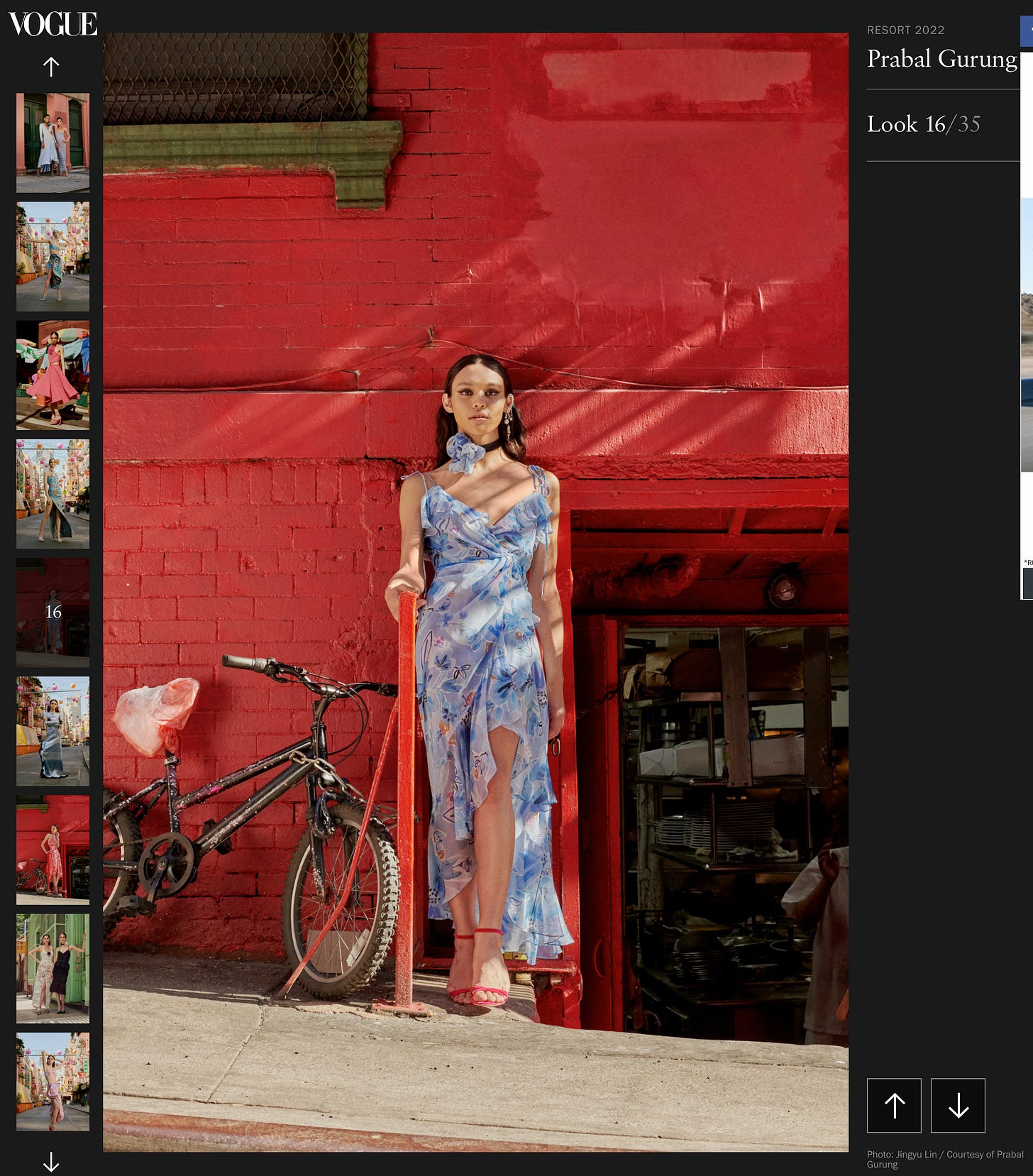

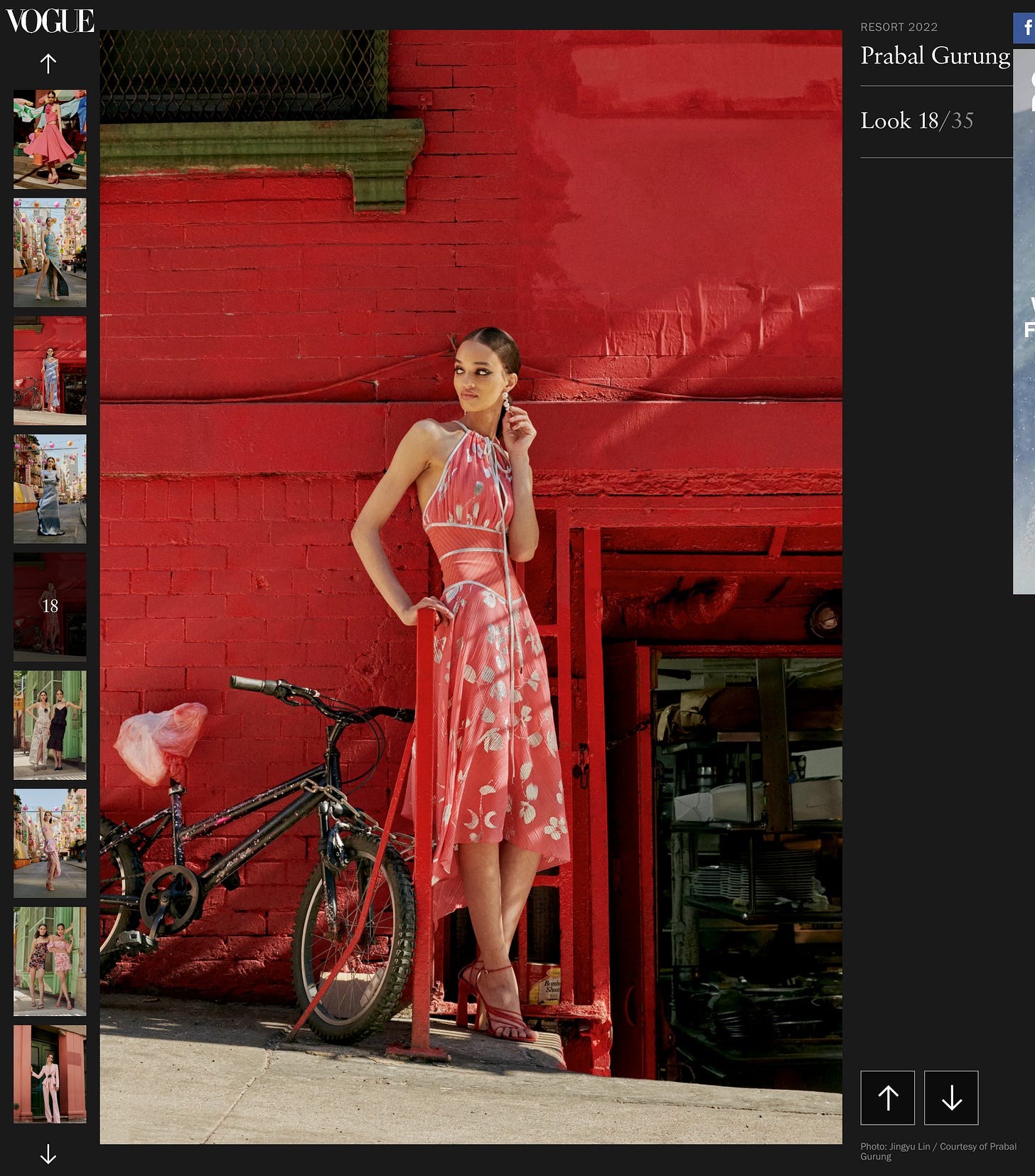

So as it pertains to the photography for this collection, I suppose the immediate question would be whether or not it is possible to reclaim Chinatown from this lens of the exotic. In earnest, I would think so should there be an intent to actually celebrate the community in such a way that it turns this consumption of the Other (à la Edward Said) onto its head. But as we will see with Looks 16 and 18, shot by Jingyu Lin, below, we have something else entirely different.

Let me point your attention to the top right of both photographs. If it looks a little odd to you in terms of texture, it’s for a good reason. Let’s take a look at the side-by-side posted by the W.O.W. Project on their Instagram stories, where it becomes pretty clear that the strange texture was a result of a clone brush not properly deployed in Photoshop to mask the original artwork and text.

The photographs capture a glimpse of a mural, titled “In the Future, Our Asian Community is Safe”, on Mosco St., which was recently painted by a group of artists, led by Jess X. Snow in collaboration with the W.O.W. Project and Smithsonian APA Center.

In a related Instagram story, Snow points out that the side-by-side of the model on the left and Mei Lum (of Wing on Wo) on the right were actually photographed on the same day, noting that “@timmych4u and I were also trying to take photos in front of this mural I painted and we were asked by @prabalgurung’s team to come back when they were done.”

From a visual studies perspective

The blatant disregard for the original artwork and its intention to acknowledge indigenous land with digital brushwork is apparent, but I also want to take a step back and reflect on what’s transpired here from the lens of visual studies to really articulate the impact of what we see by this editing choice. And to do so, I want to draw from one of my favourite texts, Roland Barthes’ 1979 work Camera Lucida and Allan Sekula’s essay entitled “The Body and the Archive”.

Barthes states that “The Photograph is violent… because on each occasion it fills the sight by force, and because in it nothing can be refused or transformed.” Of course, this text was written at a time when it would be impossible to fathom a point in time when a click of a mouse could alter an image in its entirety. So what I would posit here is that the Lin’s altered photograph (it’s not clear if Lin edited the image or if a team in post did so) still asserts itself by forcefully commanding your attention; however it instead now announces what its creator wants, as opposed to captures, to be irrefutable. In turn, there is an added dimension to the photograph where it can so easily shape-shift and transform, potentially misleading us—as opposed to leading—to what ought to be seen. Not only is the photograph inherently violent, but it has also become potentially deceptive. Running counter against Barthes’ own idea that the frame cannot be transformed, this photograph forces its new reality upon us, without so much as a mention to the actual reality.

Which in turn brings me to Sekula’s essay where we are presented with the archive (i.e. the body of records or collection of images) and its dichotomous qualities: repressive and honourific. The archive does not have to be static in quality; it can very much be in constant flux, with the potential for meaning to change over time and context. And so what we see from comments and reviews (Refinery29, WWD, Vogue) from those who do know of what has transpired is an honouring this body of work—supporting the “celebration of Chinatown” as Gurung titles it.

However, when laying context overtop these images, specifically the two that I’ve highlighted above, I would contest that this body of work quickly takes on a repressive quality at both micro and macro touch points: the immediate archive (i.e. its images) and the contextual archive (i.e. the conversation/coverage surrounding the body of work). To obfuscate what was there in the photographs not only demonstrates repression in the form of denial of visual fact, but also in the compounding of the lack of discussion at large about what should have been seen. It is to say that the invisibility that Gurung mentions in his interview with Vogue cuts so much deeper when we situate this body of work in the context of how it forces the mural’s artistic quality and message out of the frame.

Final thoughts

To tout your love for a community requires to embrace it in its entirety.

What could have been easily solved by a shifting of the framing is instead damned with the deliberate transformation of how the reality should be depicted. What could have been a love letter to a neighbourhood hit hard by the pandemic is instead nothing more than a prop. What could have been an opportunity for meaningful dialogue and larger action has instead contributed to the continued silencing of voices of a community.

I’m going conclude by simply leaving leave Jaya Saxena’s tweet here about Jenny G. Zhang’s February article for Eater. If you have the time, I’d suggest the read and maybe we can go from there.

Beautiful piece. Spot on. Gentle but thorny to the touch. Brava.