Holding Restaurant Tech Accountable

How I waged a David vs. Goliath fight and won

Disclaimer: I am not a lawyer. If you find yourself in a similar situation as the below and need legal advice, please retain proper counsel.

Earlier this week, the Los Angeles Times’ Jenn Harris highlighted Spoon by H’s encounter with credit card chargebacks, relaying an anecdote where over $700 in revenue was lost because the bank sided with the complainant. The service provider, Tock, then notified restaurant owner Yoonjin Hwang that she lost the appeal and would be on the hook for the disputed amount.

There were a lot of replies on Twitter when the story broke, ranging from: a) how the system lacks protections for these small businesses; b) to discussions of what service providers should do; and c) to empathy for struggling businesses overall. But what caught my eye and elicited my own visceral reaction was Kristin Hawley’s tweet below.

Hearing this anecdote about the onus placed on restaurants to correct and dispute platform orders brought me back to an incident last spring. One of my colleagues noticed that we were dinged $641 on Grubhub. The reason? Unconfirmed orders. However, when we clicked through the orders in question, they were all marked delivered—a snag in the system (most likely from our third-party integration that aggregates everything into one workflow) gave Grubhub a loophole to not deliver the funds owed.

With all checks and balances in place, though, one would think that the system on the delivery platform’s end would self-correct once it saw that the order was assigned a driver, picked up, and noted as delivered. It becomes apparent that this glitch, whether deliberate or not, does not favour the restaurant at all—putting the onus on a business that is trying to make it through a pandemic to make the time to reach out and resolve these problems.

What do you do about it?

When we reached out to our sales rep, she passed us along to our account manager to investigate the missing funds in question. At which point, our account manager cited a company policy that was new to us: “there is a 24-hour time frame to dispute adjustments.”

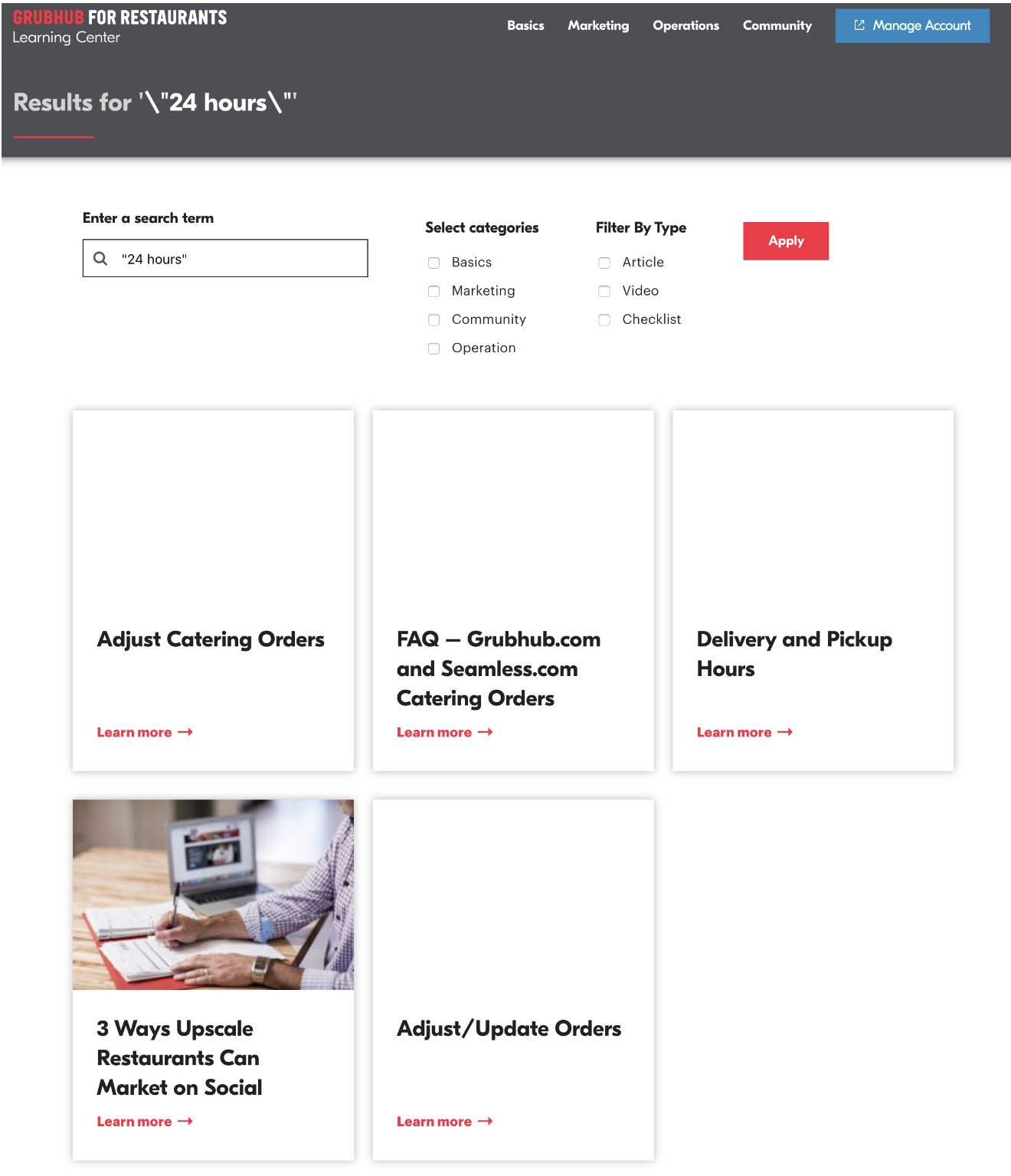

My immediate reaction was to ask myself if I missed something in the documentation. So, I quickly combed through the Restaurant Terms, our one-pager onboarding contract, and the Learning Center portal to see if there was any notice provided. And well, no, there was not a single reference to the topic on-hand to be found.

I pointed out the lack of notice, only to be told that the communication was sent “to all restaurants 11/2019 in regards to the updated refund policy and the 24 hour [sic] time frame to discuss with Restaurant Care.”

Again, leading with self doubt, I went ahead and searched mine and my coworker’s inboxes for all incoming mail from Grubhub for the period of September through December 2019, only to see one “important” email, which was about the CDC’s advisory on romaine lettuce and E.coli. For an added level of thoroughness, I also went ahead and ran a search for any emails that contained the notice’s language (which the account manager shared with us)—only her own email came back in the search results.

After submitting the above screenshots, the situation was then escalated to our account manager’s superior. To bring her up to speed, she and I had a brief call, which ended with my one ask: show me the proof that the notice was sent to us via their logs.

The follow-up email reads as follows:

Thank you for circling back. I was able to confirm that the policy update was sent out in October of 2018 - not 2019, and was not sent out as a second round. Unfortunately, we are unable to issue any sort of credit, however, because despite the policy not being emailed out every time a new account joins, it still stands as one of our policies. I understand the frustration, but again am unable to issue a credit for orders not disputed within the 24 hour time frame.

Before I get into the next part, let me clarify that we were not on the platform until 2019, so we were never going to see that email notice; in which case, the policy should never have held water, especially with what I will get at in the following analysis.

Getting into the legalese

Given that the account manager’s superior admitted that the policy was communicated only via email, and not noted anywhere else in Grubhub's Terms of Use, I countered with that rationale noting that the policy could not be enforced in this case.

Communicating a change of services has to be done via updating the Terms of Use. Per Grubhub's own Terms of Use (dated 1 January 2020), the Restaurant may be notified (but not required to); however, the Agreement must be updated to reflect these new changes. The below quote highlights the clause in its entirety.

We may change this Agreement from time to time and without prior notice. If we make a change to this Agreement it will be effective as soon as we post it, and the most current version of this Agreement will always be posted [emphasis added]. If we make a material change to the Agreement, we will notify you. You agree that you will review this Agreement periodically. By continuing to access and/or use Grubhub for Restaurants and/or any Device provided to you after we make changes to this Agreement, you agree to be bound by the revised Agreement. You agree that if you do not agree to the new terms of the Agreement, you will stop accessing and using Grubhub for Restaurants and any Device provided to you.

I go on to note that communication between Grubhub and restaurants in October 2018 of a policy change is extraneous evidence at best; it does not affect the Agreement that is in place between any restaurant onboarded after October 2018 and Grubhub unless it is posted.

If there was ever a time in which a browser wrap or implied consent scroll/button was placed for on the login page, there would be grounds for these terms; however, we had never seen such a thing. For good measure, I went ahead and requested that logs from Product be looked into to see if such a notice was ever provided.

These agreements were not particularly easy to parse, as there were three in total, each making reference to the others. Not to mention, each agreement was located on different parts of the website, thereby difficult to access.

Here are the following Terms (and the dates of when they were updated during the incident’s timeframe):

Terms of Use (dated 1 January 2020)

Grubhub Restaurant Terms (dated 15 October 2018)

Grubhub for Restaurants Terms of Use (dated 29 May 2017)

In the Restaurants Only section of Grubhub for Restaurants Terms of Use, the clause that states Grubhub may set additional terms and conditions at its sole discretion is murky at best. Fortunately, for restaurants, this clause is embedded within the paragraph about promotions, so it is specific to that condition and therefore not overarching.

Grubhub will have the right to market any and all Promos to Diners in Grubhub’s sole discretion, including, without limitation, in relation to the frequency, prominence, location (e.g. brand channels) and duration that Grubhub advertises such Promos. Grubhub may permit Restaurant to select certain Promo terms and conditions (e.g. percentage or dollar amount off, duration of the Promo, etc.). In addition to those Restaurant-selected terms and conditions, Grubhub may set additional terms and conditions in its sole discretion. Once opted into the Promo through GFR, Restaurant may not subsequently make changes to the Promo terms and conditions, and Grubhub is authorized to continue offering the Promo in accordance with such terms and conditions.

Identifying all these holes in an attempt to enforce a policy that was not communicated delivered a win of sorts. We were awarded “a one-time credit in the amount of $641 for those orders that were not addressed within the 24 hour policy window.” There was no admission of wrongdoing (because if there was, can you imagine the doors that would open for other businesses?) or apology for the inconvenience of the hours and days that it took from me to compile this position.

One of the takeaways from this mishap is to not take every answer at face value. I do not think that any of our contacts were malicious—they were trying to enforce the policies that they were told to be the rules”. However, when you have a platform that has been in business for so long, policies change and are not one-size-fits-all, especially if it isn’t communicated or updated properly.

Don’t be afraid to ask questions.

Don’t be afraid to take a look at everything that is at your disposal.

Don’t be afraid to challenge these platforms just because they’re bigger than you.

(As a side note, in an email sent on October 9, 2020, Grubhub now provides seven days for restaurants to dispute an order adjustment)

On being a decent platform partner

What I want to come back to here is Spoon by H’s run-in with the credit card dispute and subsequent loss of revenue. To be honest, I do not know a lot about credit card processors, chargebacks, and disputes, but what I do know is how to be a partner. And to be a valuable partner, especially to those in need, sometimes, you have to eat a little into your margin, per Ben’s suggestion below.

There is no wrongdoing implicated in providing a full or partial credit in good faith—all the credit demonstrates is that you hear the business’ pain and suffering, and are willing to empathize and demonstrate that these small businesses matter by tossing a bone their way.

An update on immigration policies

On Wednesday, President Biden revoked the freeze on green cards, which is said to have affected 26 000 new arrivals monthly per The Migration Policy Institute. However, temporary work visas (H-1B, H-4, H-2B, L-1, and J categories) are still on hold. Unless Biden takes steps to extend the freeze for these temporary work visa categories, the measure will expire on March 31, 2021.

Further reading:

LA Times: “LA Restaurants Struggle with a New Form of Dine-and-Dash”

Civil Eats: “As Cities Mandate Hazard Pay for Grocery Workers, Groceries Sue”

Grub Street: “Big Delivery is Winning—Even if Everyone Hates it”

New York Times: “An American Dream, Tarnished”