Ghost kitchens: consumer transparency and health regulations

Let's talk about ghost kitchens in relation to delivery platform transparency and adherence to local health codes

Let me start by saying that I’m not sure how I feel about ghost kitchens.

I talked about Popchew in Part 1 of my look at the ghost kitchen model. For Part 2, though, I want to look at the other ways in which the aforementioned exists.

It’s hard to have a singular opinion on a term that encapsulates a number of forms. Immediate permutations that come to mind of what may be defined as ghost kitchen—which does not offer indoor seating/dining for guests—include the following:

One of many private kitchens within a larger facility for small businesses to test drive ventures, while only offering delivery or limited takeout

Restaurant chains re-packaging components of their menu into a zippier and more youthful virtual-only brand

Companies in the business of creating dedicated kitchens that will cook up these virtual brands for delivery-only orders (and may offer some walk-in opportunities for takeout)

Even then, the possibility of crossover between these variations. For instance, CloudKitchens is in the business of building commercial kitchens for virtual-only brands and scaling national chains (such as Burger King, Chick fil-A, and Wendy’s). However, they are also creating opportunities for those that cannot afford their own brick-and-mortar location by way of renting out one of forty private kitchen spaces at Sunnyside Eats, as is the case for Sandra Mathis and her business, Black-Eyed Peas and Collard Greens.

Opportunities for small business owners to try their hand at an idea with lower hard costs and (presumably) brokered delivery commission deals don’t bother me. In fact, I’m all for it—you do what works for you to start your entrepreneurial path. That aspect of ghost kitchens is not something that I find to be unnerving. After all, incubator programs and commissary kitchens have been around for ages (albeit without the availability an online ordering and delivery component, which marks the distinction of what makes a ghost kitchen a ghost kitchen).

What I find troublesome about ghost kitchens, though, are the recurring themes of a lack of transparency and regulation enforcement when we move outside the conversation of helping the solo business operation.

Missing disclosures and deceptive marketing

Hop on to the delivery platforms and search for MrBeast Burger, would you? Depending on which platform you’re using, there may or may not be a disclaimer advising you that this restaurant chain is a virtual one.

Out of the big three delivery platforms, only DoorDash has a banner disclosing MrBeast Burger’s status as a virtual brand. But if there are other promotions at play (such as BOGO), you’ll have to click through the carousel to get your disclaimer.

Conversely, with both Uber Eats and Seamless/Grubhub, neither platform acknowledges that MrBeast Burger is a virtual concept on their respective store pages. For unsuspecting users, it’s easy to mistake MrBeast Burger for your local brick-and-mortar restaurant in the city.

And while DoorDash’s labeling in this instance is extremely clear, the company does experiment with levels of transparency and consumer knowledge by varying language on its banners, depending on whose ghost kitchen concept it is.

Take Lucky Dragon Fried Rice for instance. Yes, it is a virtual brand, but it receives a slightly different banner treatment: “A concept by Nextbite”.

Similarly, It’s Just Wings and Tender Shack carry banners that simply tout “A concept by Brinker International” and “Off-menu favorites from Bloomin’ Brands” respectively. And to be candid, the last two disclaimers were only added this week, as I hadn’t noticed them two weeks ago when I started working on this newsletter.

And then there’s Wow Bao who goes one step further with their banner saying “Wow Bao partners with neighborhood restaurants to offer a virtual Wow Bao and give you even more delicious options.”

These descriptions sound innocent enough, but they do not provide the full context of the businesses behind these food ventures. Of the examples mentioned, let me break it down for you:

Nextbite is a company that specializes in virtual restaurant concepts, so it doesn’t make sense why they have a special label instead of the good ol’ “This is a virtual brand” banner

It’s Just Wings is a slimmed down and re-branded menu offering from Chili’s—but saying the parent company name doesn’t ring as many bells as, well, Chili’s

To compete with Brinker, The Outback Steakhouse’s parent company launched a similar initiative: Tender Shack

Wow Bao is a national chain that has a whole page on its website dedicated to its dark kitchen model where other ghost kitchens and local restaurants can earn additional dollars by moonlighting as a steamed bun and dumpling shop

If you want to buy from a ghost kitchen, that’s cool—again, I say you do you. But I feel that consumers should be well informed about who they are supporting, whether it be ghost kitchen, franchisee, chain restaurant, or independent business. Scaling language up and down, depending on the leverage the preferred partner has not only furthers an imbalanced marketplace, but also preys on uninformed consumers.

At least with all other ad units (such as higher ranked listings and placements), they are marked as sponsored. These banners, with their flowery language, do not, and are in turn highlighting DoorDash’s biases toward and possible partnerships with certain companies.

And when we talk about the re-branding and -packaging of legacy brands, such as Chili’s, into slimmer menus that hone in on a certain type of food, it becomes apparent that part of this strategy is not only to make the parent company relevant again, but also to own more digital real estate on the third-party delivery platforms. After all, more brands and more listings mean more chances to be found. As Kristen Hawley’s 2020 (yet still very relevant) Eater article highlights: “[i]nstead of a huge menu where some items might get lost, those items can be broken out and highlighted as brands of their own, a benefit for existing restaurants looking to make more money.”

In some ways, this form of competition is not unlike the “ghost restaurants” of 2015 where multiple listings were created for restaurants to game the system in search and opportunity. Except in this case, the ones inflating their chances for business are the companies who have the fiscal and human capital resources to invest into branding materials and completing the necessary paperwork.

Compliance with local health regulations

In mid-March, Insider released an article that detailed how Reef, known for its modular kitchens, had flouted regulations by operating without proper insurance, licenses, and permits. Even though the article looks at operations in Miami and Houston, it is still cause for concern when large-scale city operations like those fail to adhere to the laws and guidelines set forth by their respective cities.

In addition, it was noted that many customers had complained of raw or undercooked food. Not to mention, Reef insiders highlighted a series of safety issues, such as a lack of potable water and “fireball-emitting propane stoves.”

The lack of quality control and assurance has gone so far that Fuku, who didn’t outright say why the partnership ended, dropped Reef as its national growth partner. Instead of relying on a company to oversee all operations, Fuku has teamed up with Kitchen United, whose approach relies on making restaurant brands responsible for food preparation and merely rents out the infrastructure.

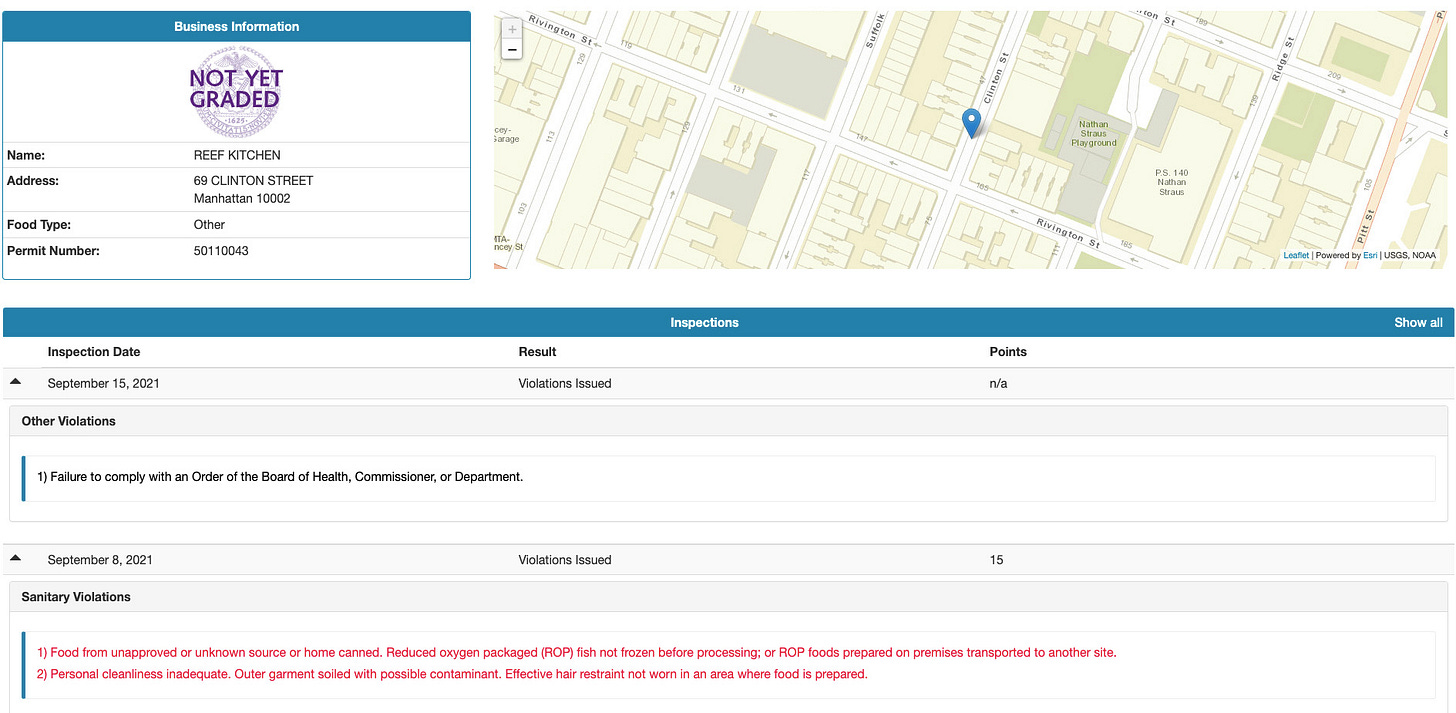

Taking a look at New York’s ghost kitchens, the only one with glaring infractions was located at 69 Clinton St. in the Lower East Side. Covered in DJ Khaled’s Just Another Wing-branded window decals, this address is home to a Reef kitchen, according to the NYC Department of Health (DOH). Now, even though I’ve been with Nom Wah for a decade, I still have yet to obtain my Food Handlers card, so I had Ms. Julie (as I call her) help me with my homework in deciphering the violations.

September 15, 2021: Failure to comply with an Order of the Board of Health, Commissioner, or Department.

Julie said that this was the first time she’s ever seen a violation like this one. It is normal (and within reason) to let the inspector know that you are not the manager and are therefore not permitted to give them the tour, but will grab the on-site manager to conduct the inspection. Unfortunately, this violation was not the case. What “failure to comply” means in this instance is that the on-site employee declined to even let the inspector in. It’s not a great look to say the least with regards to compliance for local regulations and transparency for customers.

September 8, 2021: Personal cleanliness inadequate. Outer garment soiled with possible contaminant. Effective hair restraint not worn in an area where food is prepared.

When I placed a pickup order from a Reef kitchen a few weeks ago, I was able to take a quick glimpse inside when my order came out. The entirety of the ground floor of 69 Clinton is retrofitted to be a kitchen upon entry—kitchen equipment on the right and shelves of goods on the left. There isn’t a receiving room in the front, nor is there any space for delivery folks to wait inside. It was also on that day that I noticed there was only one person working, which may not always be the case, although it may explain the lack of accountability on personal cleanliness, as noted in this violation. Julie also commented that she would consider this lack of personal hygiene to be a huge red flag in the kitchen, as it may also be an indicator of other kitchen and cooking processes not meeting standards that may not have been apparent during an inspection.

And let’s also not forget that Reef closed its New York kitchen vessels in Q4 of last year due to the city stating that it found numerous rules and requirements were not followed.

Other ghost kitchen outfits either have not yet been inspected due to the newness or are currently operating out of a smoothly-run restaurants, as is the case of Nextbite’s Lucky Dragon Fried Rice, which shares its address and DOH permit with L’Entrée at 293 Church St. It’s not a surprise that the ghost kitchen operations by those who already have experience by operating an actual restaurant are less likely to have violations than those who are completely new to both the business of food and operating a food business under stringent regulations.

Growing the business of food with ghost kitchens

Scaling without oversight into the kitchen operations poses a significant challenge. As we saw, Fuku pulled the plug on letting the ghost kitchen operator be in the driver’s seat. Other large scale chain operations, such as Brinker International and Bloomin’ Brands, operate out of their already established ecosystem to introduce new virtual brands. Even the “simple” items, such as burgers and wings, require a standard, which isn’t something that a ghost kitchen company is necessarily equipped to handle or enforce.

For example, in tasting the two MrBeast Burger meals that I ordered from two different ghost kitchens, the amount of seasoning or squish on the smash patties were inconsistent. Fries received a similar treatment in which there was inconsistency in the amount of seasoning that should be applied in each box. Offerings, too, were inconsistent—different brands of bottled water; it’s not something that you would see at this scale of business where it’s agreed upon at the national level (or at least regional) what condiments or beverages to dispense. MrBeast Burger may very well be a brand, but it doesn’t have a process for executing its brand. And that’s something a ghost kitchen setup can’t easily address when they don’t actually work for said brand specifically and are cooking up several other virtual ones.

Overall, like ordering from anywhere, your mileage may vary depending on which ghost kitchen operation is making your food. As another example, I found C3’s Krispy Rice branding and food to be solid, even if I could only sample from one location (but I opted for a few items to test out the consistency). But again, the DOH notes that they aren’t in a Reef kitchen, churning out multiple brands, but rather, their own (shared with Proper Food).

Look, I don’t think I’d go out of my way to order from a ghost kitchen, but I certainly would like to have the agency to decide where I am doing so or not. Even though delivery platforms so integral to the success of ghost kitchens, they are also a must in the case of many independent restaurants. The delivery platform needs to have some accountability in who they showcase, especially so much of their sales talk is about helping the little guy. By labeling the virtual brands explicitly and consistently, we can at least level the playing field a little bit and let the consumer make their own informed choices. No need to tell us who your favourite child is, DoorDash.